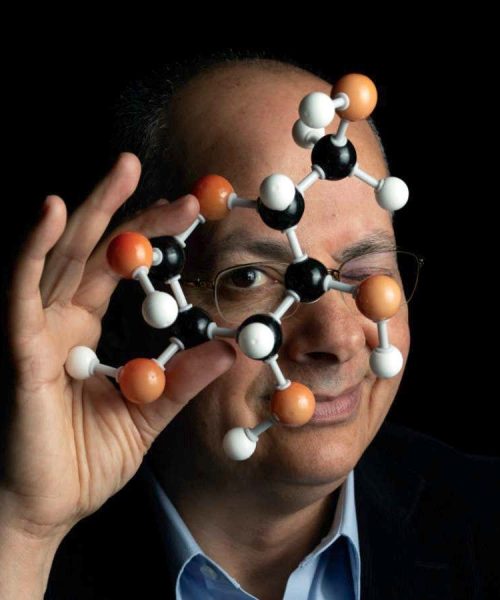

Paul Ryding

According to Thomas Hobbes, one of history’s most famous cynics, life is “nasty, brutish, and short”. But according to Jamil Zaki, director of the Stanford Social Neuroscience Laboratory in California, this is, ironically, more likely to be true if you have a cynical, Hobbesian outlook on life, seeing the worst in humanity and failing to trust anyone.

Zaki didn’t always think this way. He has studied and lectured on the brain circuitry behind empathy and kindness for two decades, all the while harbouring a dirty secret: he was a cynic. It was after the death of his friend Emile Bruneau, who studied the neuroscience of peace and conflict and was “one of the most hopeful people I ever met”, says Zaki, that he began to examine his cynical perspective. He discovered that cynicism is not only harmful to our lives, but also makes us believe things that aren’t true. Luckily, there are tools we can use to combat our cynicism, as he explores in his upcoming book Hope for Cynics: The surprising science of human goodness.

Alison Flood: What is cynicism?

Jamil Zaki: Cynicism is a theory that, in general, humanity is selfish, greedy and dishonest. Theories power our behaviour, what we do and what we don’t do. So cynics use their theory about people to guide their behaviour in the social world. It changes what they see, it changes how they interpret other people and it changes what they do, such as not trusting others.

How does cynicism differ from scepticism?

That’s really important.…