Martin Shields/Alamy

Could you run for 100 hours this year? How about just doing a little more than 15 minutes each day? In fact, these goals are essentially equivalent, but one certainly sounds more ambitious than the other.

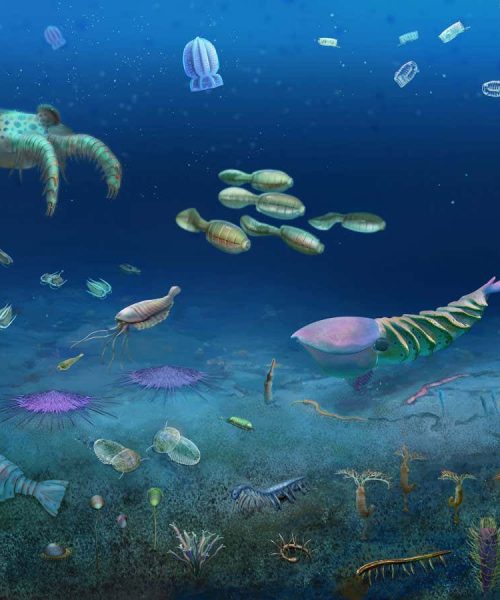

The correct framing, then, is important when setting a goal. Take averting a sixth mass extinction. It definitely sounds hard. Mass extinctions are devastating events – there is no precise definition, but these are broadly understood as leading to the loss of about 75 per cent of all species on Earth over the course of at least several thousand years. And yet, some people argue that stopping one is easy.

That is because, while humanity has certainly caused catastrophic biodiversity loss, even if extinction rates remain as high as they are today, it would take us centuries to wipe out three-quarters of species.

Advertisement

According to John Wiens at the University of Arizona (see “There’s growing evidence the big five mass extinctions never happened”) and others, avoiding a textbook extinction could still be devastating. “We could lose half the species on the planet over the next 3000 years and still say, ‘Yeah, we did it! We prevented the sixth mass extinction,’” he says.

We could lose half of all species over the next 3000 years and still say, ‘Yeah, we did it!’

Instead, he argues that we should aim to prevent human-induced extinction from hitting 0.2 per cent of species – a far cry from the 75 per cent needed to qualify for a mass extinction, and the equivalent of boosting that annual 100-hour running target to more than 100 hours a day, which certainly would be a challenge.

Wiens’s target is far from impossible, however – merely very difficult – and his questioning of the framing of the “sixth mass extinction” is an attempt to focus on conserving vulnerable species today, rather than centuries from now.

But the approach isn’t without controversy; his questioning of the definition of mass extinction could be seen by some to undermine the argument that we are facing one now. Should we, then, just stick with the label? Doing so would arguably be the easy choice. But by highlighting their concerns, Wiens and colleagues have chosen the harder – and perhaps better – option.

Topics: