Coke Navarro

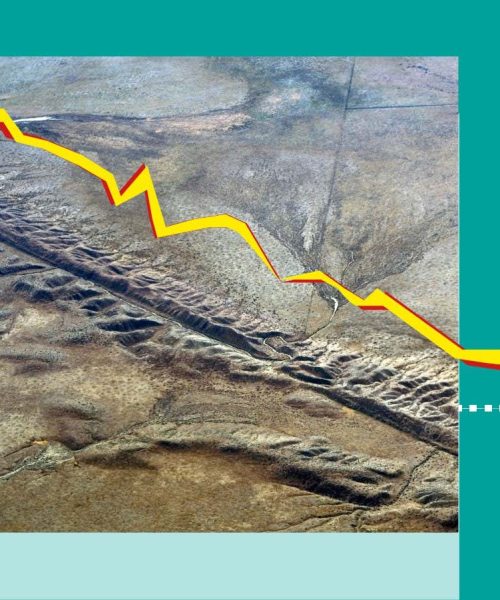

Ramesses III was one of Egypt’s great warrior pharaohs. A temple he built at Medinet Habu, near the Valley of the Kings, highlights why. On its walls, carvings tell the story of a coalition of fighters that swept across the eastern Mediterranean 3200 years ago, destroying cities, states and even whole empires. “No land could stand before their arms,” this account tells us. Eventually, the invaders – known today as the Sea Peoples – attacked Egypt. But Ramesses III succeeded where others had failed and crushed them.

In the 200 years since hieroglyphics were first deciphered, allowing us to read Ramesses III’s extraordinary story, evidence has come to light to corroborate it. We now know of numerous cities and palaces across the eastern Mediterranean that were destroyed around that time, with the Sea Peoples often implicated. So widespread was the devastation that, for one of the only times in history, several complex societies went into a steep decline from which they never recovered. Little wonder, then, that this so-called Late Bronze Age collapse has fascinated scholars for decades. So, too, has the identity of the mysterious sea-faring marauders.

Today, new genetic and archaeological evidence is giving us the firmest picture yet about what really went on at this dramatic time – and who, or what, was responsible. This shows that many of our ideas about the Sea Peoples and the collapse need completely rethinking. It also hints at a surprising idea: the end of civilisation might not always be as disastrous as we think.

Before the Sea Peoples arrived, life…