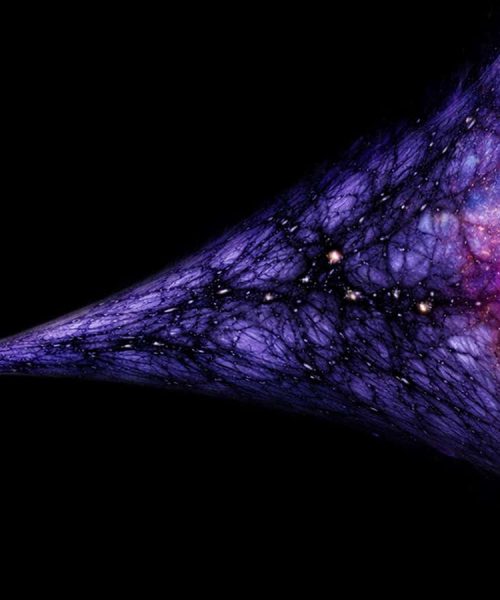

We may never know the universal wave function

VICTOR de SCHWANBERG/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Getty Images

From the vantage point of quantum physics, the universe may in some ways be fundamentally unknowable.

In quantum physics, every object, such as an electron, is matched to a mathematical formula called the wave function. The wave function encodes all the details of an object’s quantum state, which means physicists can predict what an object might do in an experiment by combining its wave function with other equations.

But if we accept that the whole world is quantum – and many researchers do – then much larger objects ought to have wave functions, including the whole universe. This is a point of view that was previously argued by, for instance, physics luminaries like Stephen Hawking.

Now, however, Eddy Keming Chen at the University of California, San Diego, and Roderich Tumulka at the University of Tübingen in Germany have proved that complete knowledge of this universal wave function may be fundamentally inaccessible.

“The wave function of the universe is like a cosmic secret that physics itself conspires to keep. We can know enormously much about how the universe behaves, yet remain fundamentally uncertain of which quantum state it is in,” says Chen.

Previous studies posited the universal wave function’s form based on theoretical models of the cosmos and didn’t directly address what role experiments and observations could play in determining its details. Chen and Tumulka started with a more pragmatic question: given some set of wave functions that could reasonably represent our universe, could observations enable researchers to pick out the correct one?

The pair started with mathematical results from quantum statistical mechanics, which studies properties of collections of quantum states. Another ingredient in their calculations was the fact that the universal wave function would require a very large number of parameters, or exist in an abstract state with many dimensions.

Strikingly, upon completing the calculations, the team had to conclude that the universal quantum state is essentially unknowable.

“Any measurement that’s allowed according to the rules of quantum mechanics will give us very limited information about the wave function of the universe. It’s impossible to determine the wave function of the universe with any useful accuracy,” says Tumulka.

JB Manchak at the University of California, Irvine, says this work helps us better understand the limitation of our very best empirical methods and already has some counterparts in general relativity – Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity. At the same time, this may not be surprising, as quantum theory was never conceived as a theory for cosmically large scales, he says.

“The wave function, of a small system or of the entire universe, is a rather theoretical entity. Wave functions are relevant, not because we see them but because we use them,” says Sheldon Goldstein at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He says that this means it may not be a problem that we are unable to choose a single most accurate universal wave function from a narrow set of candidates, because any of the wave functions in the set may have a similar effect when used in further calculations.

Chen says that he and Tumulka now want to connect their work to large systems that are smaller than the whole universe, and especially to investigations into techniques like “shadow tomography”, which are used to determine such system’s quantum states. But the work’s philosophical implications matter as well. Specifically, researchers should take it as a note of caution to not overly rely on positivist thinking, or the notion that a statement is meaningless or unscientific if it cannot be tested experimentally, says Tumulka. “Certain things actually exist out there in reality, but we cannot measure them,” he says.

This reasoning may also play into the century-long debate on how to make sense of quantum mechanics itself, says Emily Adlam at Chapman University in California. In her view, the new result can be seen as motivation to put more stock into interpretations of quantum equations, such as the wave function, that emphasise relationships between quantum objects and each observer’s perspective rather than positing one objective view of reality codified by a single mathematical object.

Topics: