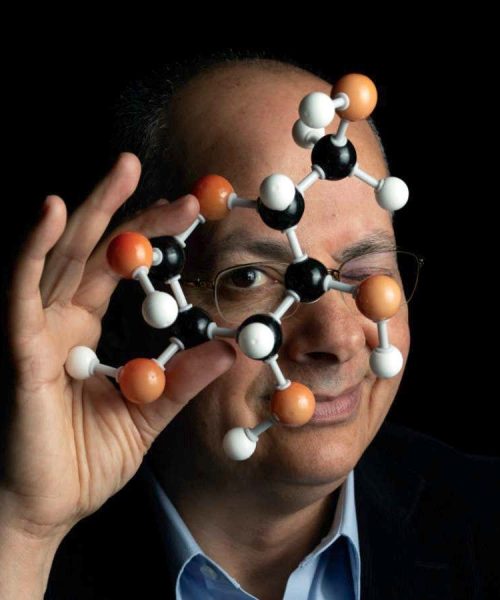

Kolotuschenko/iStock

The severed pig’s head had come from the local abattoir. It would have typically been discarded, but Zvonimir Vrselja, a neuroscientist at Yale School of Medicine, and his colleagues had other ideas. Four hours after this particular animal was decapitated, they removed its brain from its skull. They then connected the dead brain’s vasculature to tubes that would pump a special cocktail of preserving agents into its blood vessels and turned the perfusion machine on.

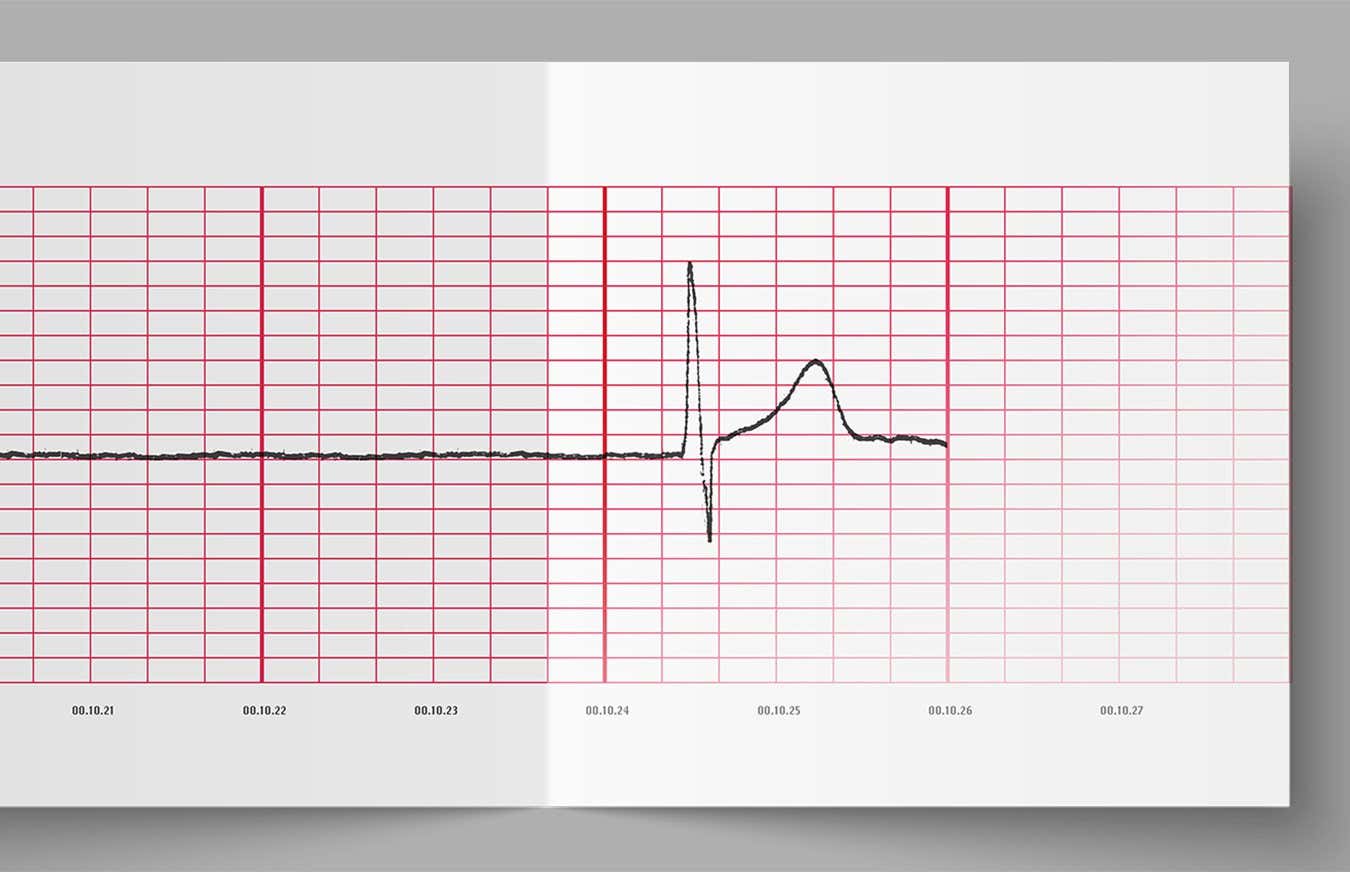

That was when something incredible happened. The cortex turned from grey to pink. Brain cells started producing proteins. Neurons juddered back to life, displaying signs of metabolic activity indistinguishable from that of living cells. Basic cellular functions, activities that were supposed to irreversibly cease after blood flow stopped, were restored. The pig’s brain wasn’t alive, exactly – but it certainly wasn’t dead.

Now, for the first time, the team is using the technique on human brains.

“We are trying to be transparent and very careful because there’s so much value that can come out of this,” says Vrselja. Reanimating – in a sense – a dead human brain would have tremendous medical benefits. Researchers could trial drugs on cellularly active human brains, leading to improved treatments. Similar techniques are already being used to better preserve other human organs for transplants, too. And in what is perhaps the most immediately useful application, the resuscitation technology involved raises the possibility of saving people on the cusp of death.

The problem is that it is an ethically complicated undertaking, to put it mildly. And by…