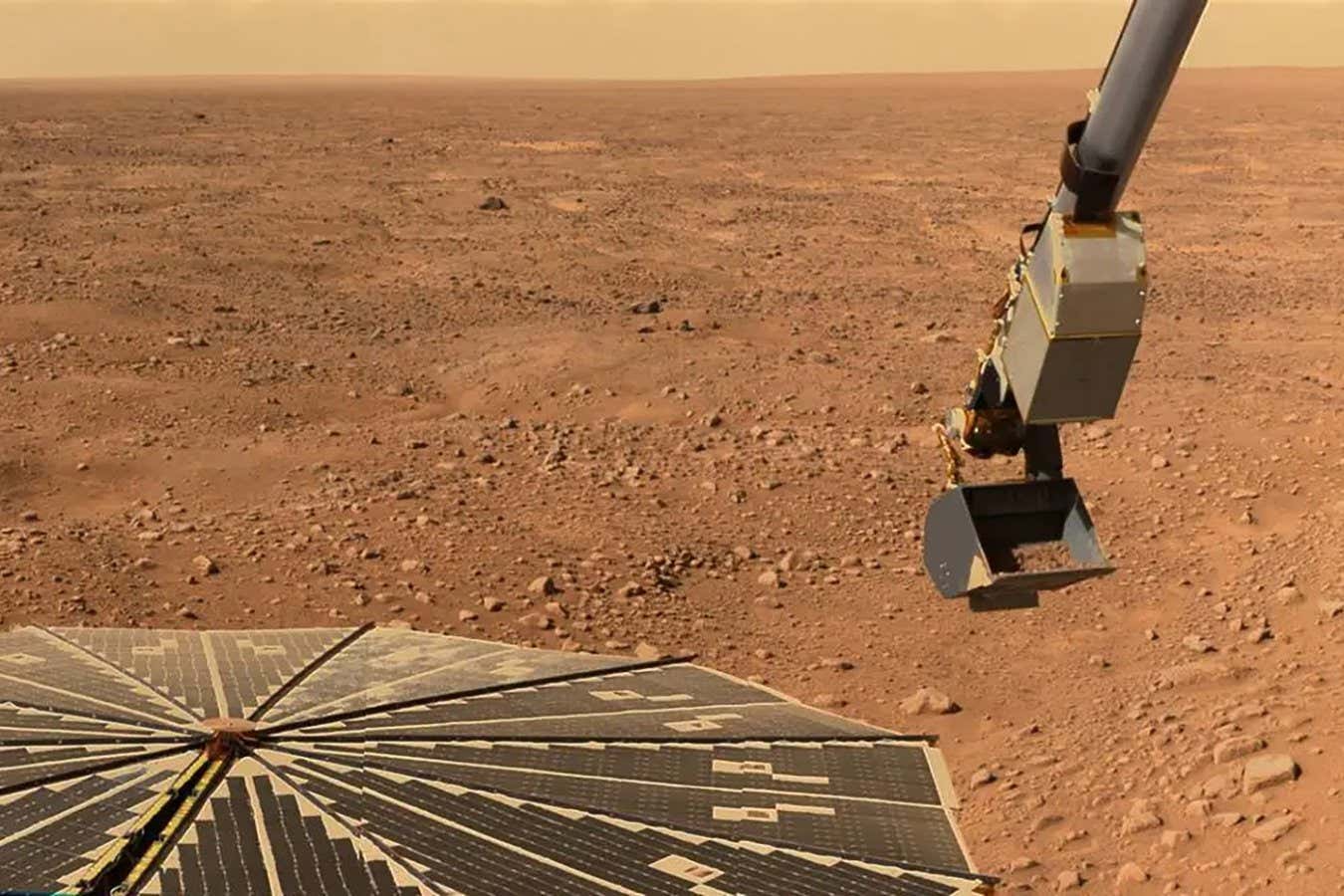

NASA’s Phoenix Lander’s solar panel and robotic arm with a sample in the scoop

NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/Texas A&M University

Mars may have a network of liquid water flowing through the frozen ground. All buried permafrost, on Earth and beyond, is expected to host narrow veins of liquid, and new calculations show on Mars, they could be big enough to support living organisms.

“For Mars we always live on the edge of maybe habitable, maybe not, so I set out to do this research thinking maybe I can close this loop and say that it’s very unlikely to have enough water and have it be arranged so that it’s habitable for microbes,” says Hanna Sizemore at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona. “I proved myself wrong.”

She and her colleagues used measurements of the soil composition on Mars to calculate how much of the icy soil could actually be liquid water and the size of the channels that water would run through. It is tricky to keep water liquid on Mars, because temperatures can get as low as -150°C (-240°F) on the planet. While pure water freezes at 0°C, the abundant salts on Mars can dissolve in the water there and lower its freezing point significantly.

The researchers found that it was “surprisingly easy” to get soil with more than 5 per cent liquid, running through channels at least 5 microns in diameter – the requirements they set for the veins to be considered habitable. “The largest veins we’re talking about are 10 times narrower than very fine human hair,” says Sizemore. “But it’s a large enough environment to submerge a microbe, and [they are] connected enough to move food and waste through the environment.”

Based on soil measurements from NASA’s Phoenix spacecraft, which landed on Mars in 2008, these networks of channels could be abundant at latitudes higher than 50 degrees. If there is life on Mars, the liquid veins would be the easiest place to look for it, says Sizemore: “This is an environment where we can land and dig down like 30 centimetres and sample this.”

The main potential problem with these veins as habitable environments is their temperature, which can be much colder than most known lifeforms can tolerate. “We have to be careful, though, about using the limits in which terrestrial life can grow and metabolise, as they do not necessarily represent the limits in which any life, anywhere, could function,” says Bruce Jakosky at the University of Colorado Boulder. “The bottom line is that, based on this and related work in particular, it’s not impossible that life could exist in the Martian near surface.”

Topics: