Stephan Walter

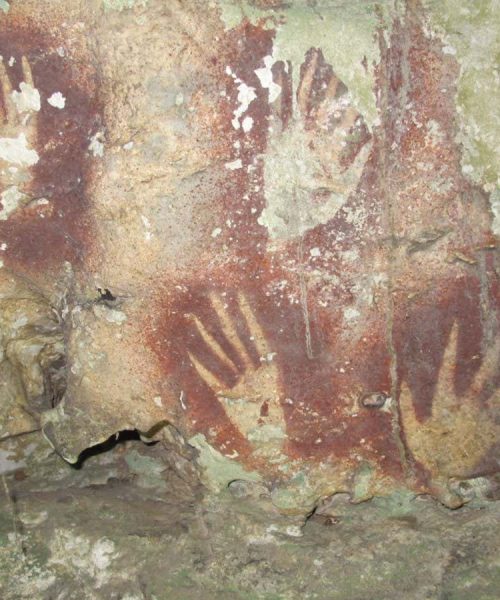

What has happened in the field of human evolution over the past 25 years can be summed up in one word: “more”. Archaeologists have found many more fossils, species and artefacts, in more places – from diminutive “hobbits” who lived on an Indonesian island to the mysterious Homo naledi known only from a single deep cave in South Africa. In parallel, researchers have developed more and better techniques for analysing all these remains. There is, quite simply, a huge amount of information about our origins and extinct cousins.

Two major lessons have emerged from this blizzard of discoveries. First, since 2000, the hominin fossil record has been extended much further back in time. In the late 1990s, the oldest known hominin was the 4.4-million-year-old Ardipithecus. But in 2000 and 2001, researchers found an even older Ardipithecus, Orrorin tugenensis from 6 million years ago and Sahelanthropus tchadensis from 7 million years ago. A second Orrorin species, Orrorin praegens, was quietly described in 2022; it seems to be a little more recent than O. tugenensis.

The discovery of these early hominins was “one of the big revolutions”, says Clément Zanolli at the University of Bordeaux in France.

Second, the story of our own species’ emergence from the hominin pack has become far richer. By 2000, genetic evidence had demonstrated that all non-African people are descended from African ancestors who lived about 60,000 years ago. The implication was that modern humans evolved in Africa and then expanded from there, replacing all the other hominin species.

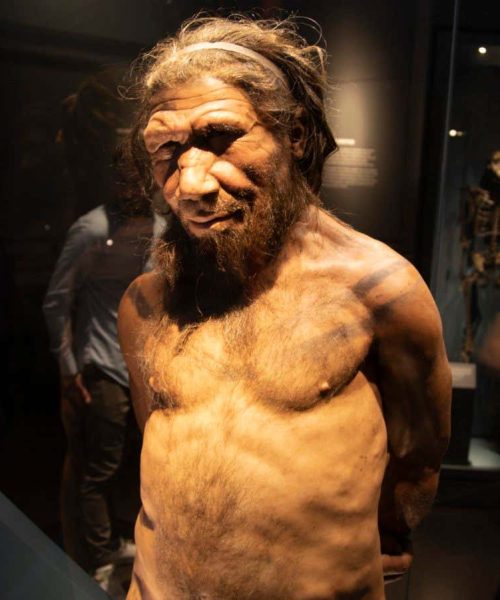

However, in 2010, researchers sequenced the first Neanderthal genome, and DNA from many other ancient humans has followed. The DNA revealed that our species interbred with Neanderthals, Denisovans and possibly others – and that other groups were also sometimes mixing.

Researchers who study skeletons had long suspected interbreeding, because many fossils don’t neatly fit species categories, says Sheela Athreya at Texas A&M University in College Station. A jawbone from Peştera cu Oase in Romania was described by Erik Trinkaus and his colleagues in 2003 as a human-Neanderthal hybrid, based on its shape. “[Trinkaus] was called a crackpot,” says Athreya. Then, in 2015, genetics revealed that the Oase individual had a Neanderthal ancestor four to six generations previously.

Our species didn’t simply expand out of Africa, then. Instead, our population absorbed the genetic heritage of Neanderthals and Denisovans along the way. Genetically, we are a patchwork: the stitched-together remains of millions of years of diverse forms of humanity.

Topics: