Josie Ford

Wins for kids

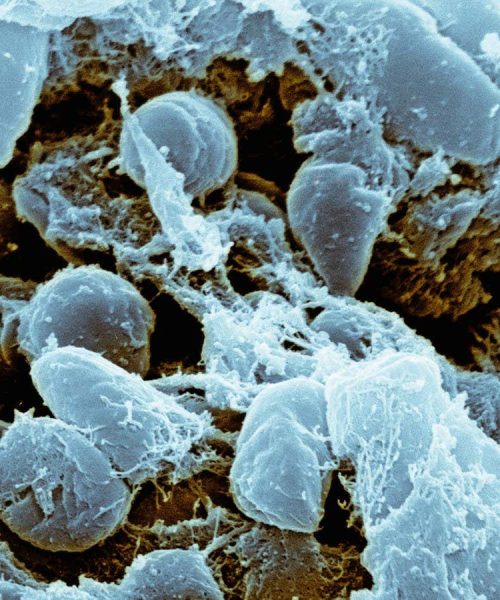

Spectator sports are good for children – good for creating children, that is – according to data in a study by Gwinyai Masukume at University College Dublin, Ireland, and his colleagues.

That data pertains to major American football, Association football (soccer) and rugby union tournaments in Africa, Asia, Europe and North America.

“With a few exceptions,” say the researchers, these popular contests “were associated with increases in the number of babies born and/or in the birth sex ratio 9(±1) months following notable team wins and/or hosting the tournament”.

Advertisement

Sports events on this level seem to work that way for winners – but not for losers, says the study, which was published in the journal PeerJ. The downside is, no kidding, substantial: “unexpected losses by teams from a premier soccer league were associated with a decline in births 9 months on”.

Celebratory sex

That spectator-sports study begins with a seductive sentence: “Major sporting tournaments may be associated with increased birth rates 9 months afterwards, possibly due to celebratory sex.”

Not many researchers focus on the topic of celebratory sex. But four scholars at the University of South Dakota did, in a 2017 paper called “Sexual behavior in parked cars reported by Midwestern college men and women“.

The foursome write candidly about their observations: “[Some people] would plan ahead for days or weeks for a leisurely, lengthy parking session of ‘celebratory’ sex for birthdays, holidays, graduations, proms, or ‘breaking in’ a new car… sex while parked was primarily a positive sexual and romantic experience for both men and women.”

The study’s abstract climaxes with a simple thought: “The future study of sex in parked cars in urban environments is recommended.”

Timeliness of time

The eternal question “What is time?” has staggered doubly to centre stage – first in a Finnish report about Russian time zones, second in a shifty action by the nation of Kazakhstan.

Nelli Piattoeva and Nadezhda Vasileva at Tampere University in Finland wrote a 20-page assessment called “Taming the time zone: National large-scale assessments as instruments of time in the Russian Federation“.

Russia has 11 time zones. Piattoeva and Vasileva instruct us that: “The presence of multiple time zones evidences the lack of a unified spatio-temporality.” And they express a thought that no one has ever quite put into clear words: “Bureaucratically, the desire for simultaneity and synchronicity takes the form of a meticulous ordering of a sequence of actions through prescriptive documentation.” They reveal that there is a hinge to everything: “In our analysis, we reverted repeatedly to the most difficult question of all: what is time?”

Independently, the government of Kazakhstan added clarification, wonder and, maybe, confusion to the general timely mix. On 1 March, Kazakhstan rendered its two time zones down into a solitary, nationwide time zone.

The Times of Central Asia reported, two weeks prior to the big day, that “not all citizens are happy about it, with some arguing it will impact their health”. The Times interviewed Sultan Tuleukhanov at Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, who warned: “There is such a concept as desynchronises, a type of inconsistency. In particular, it’s a change to the chrono-structural parameters of biological rhythms of the human organism.”

Feedback salutes the boldness, if nothing else, of anyone who dares monkey with the chrono-structural parameters of biological rhythms of the human organism.

Unread, un-existent

How many research studies that nobody had read… eventually just disappeared? And how many studies that have disappeared… had never been read by anybody, even before disappearing? Rough answers to both questions – they are not quite the same question! – now exist.

The first question got addressed almost two decades ago, when Lokman I. Meho at Indiana University Bloomington published a paper (which hasn’t yet disappeared) called “The rise and rise of citation analysis“.

Meho wrote: “It is a sobering fact that some 90% of papers that have been published in academic journals are never cited. Indeed, as many as 50% of papers are never read by anyone other than their authors, referees and journal editors.”

The second question got a good going-over by Martin Paul Eve at Birkbeck, University of London. His new study (which also hasn’t yet disappeared) is called “Digital scholarly journals are poorly preserved: A study of 7 million articles“. The study did an “appraisal” of 7,438,037 scholarly citations that have unique identification codes called DOIs. Well, the study attempted to do an appraisal. Eve reports that 2,056,492 (27.64 per cent) of those items appear to be missing.

Eve also says that 32.9 per cent of the organisations responsible for digitally preserving documents “seem not to have any adequate digital preservation in place”.

Feedback celebrates and laments that this deepens the meaning of an old ideal: that research should raise more questions than it answers.

Marc Abrahams created the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony and co-founded the magazine Annals of Improbable Research. Earlier, he worked on unusual ways to use computers. His website is improbable.com.

Got a story for Feedback?

You can send stories to Feedback by email at feedback@newscientist.com. Please include your home address. This week’s and past Feedbacks can be seen on our website.

Topics: