Bhumi and Belle, a mother-daughter pair of marmosets

David Omer Lab

Marmosets use unique calls for other monkeys in their family groups, similar to how humans call each other by name. They are the first non-human primates known to do so. This discovery shows that communication in marmosets is more complex than previously thought, and it could help teach us more about how human language evolved.

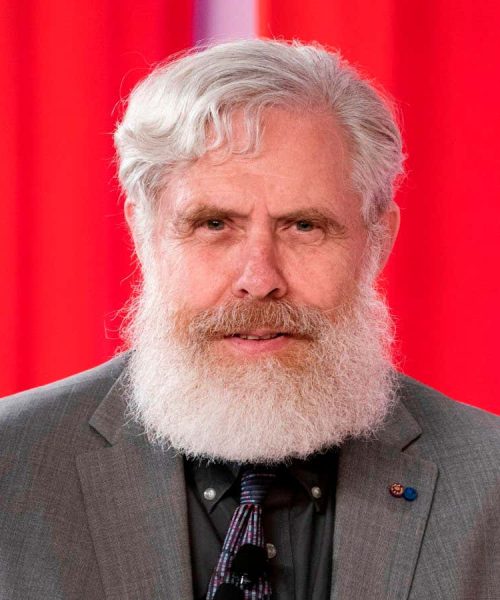

“Up till quite recently, people thought that human language is a singularity phenomenon that popped out of nothing,” says David Omer at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “We’re starting to see evidence that this is not the case.”

Advertisement

Marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) live in tight-knit, monogamous family groups and spend their lives shrouded in dense rainforest canopies, so they use high-pitched, chirpy melodies that carry through the foliage to convey information to each other, such as their location. Listen below:

–>

–>

Omer and his team analysed how these high-pitched “phee calls” also help the monkeys map their social circles in their brains. In the lab, they recorded phee call exchanges between pairs of marmosets separated by a screen. They paired up 10 marmosets from three different families in a variety of combinations, then used artificial intelligence to sort more than 50,000 calls they made into different categories according to subtle acoustic differences. Later, they observed how three of those marmosets reacted to the lab recordings of phee calls both directed to them and to others.

The team found that marmosets make 16 types of subtle acoustic tweaks to their phee calls according to which monkey they are addressing, encoding specific information about who they are directing the call towards. They intersperse these monkey-specific modulations throughout the call – in human language, it would be akin to interjecting sounds that convey a friend’s name throughout a sentence. Marmosets on the receiving end of these calls respond much more quickly and reliably to those directed to them than to others, meaning they understand that they are being called on, says Omer.

This initial analysis also suggests that family members use similar identifying labels for the same monkey as if it were a designation distinct to them, like their personal name, and not just vague identifying information.

If marmosets indeed use unique personalised names, they would have to be learning how to make the specific acoustic characteristics the names entail, says Daniel Yasumasa Takahashi at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte in Brazil. This implies marmosets have a more flexible vocal system than previously thought, he says. But to truly show that the marmosets are learning the unique identifiers from one another, researchers would still need to find that marmosets didn’t know these identifiers before joining a social group, and that they learn them by listening to dialogues between other monkeys and imitating them.

These findings also pose the question of whether marmosets can label other objects vocally too – and because naming people, places and objects is a fundamental property of language, it could help us pinpoint when that began to evolve.

A growing body of studies suggests that a variety of unrelated animals might be calling each other with identifiers, including a few species of parrots, African savannah elephants and possibly Egyptian fruit bats. That suggests name-calling has cropped up independently across the tree of life, and there might be similar social selection pressures in the ecology or society of these animals that cause names to evolve, says Michael Pardo at Colorado State University, whose research discovered that common bottlenose dolphins have name-like identifiers.

“Many animals are a lot more cognitively sophisticated and have much richer social lives than has historically been recognised,” he says.

Topics: