Unlike extinct woolly mammoths, most edited elephants with mammoth-like traits would have no tusks, to get around ivory poaching

QuangTrungArt/Shutterstock

A company set up to resurrect extinct animals says it has achieved a major breakthrough in its goal of bringing back the woolly mammoth. On 6 March, Colossal announced that its team had managed to turn normal elephant cells into stem cells, which could lead to a mammoth-like creature. “This is a momentous step,” its CEO, Ben Lamm, said in a press release. Here’s what you need to know.

Is it really possible to bring the woolly mammoth back from extinction?

No it isn’t and never will be. While the genomes of several frozen mammoths have been sequenced, these are riddled with gaps. However, it should be possible to edit the genomes of living elephants to make them mammoth-like. Colossal acknowledges on its website that what it plans to create will be “a cold-resistant elephant”, but says the animal will have “all the core biological traits of the Woolly Mammoth”.

Advertisement

Will these edited elephants look like mammoths?

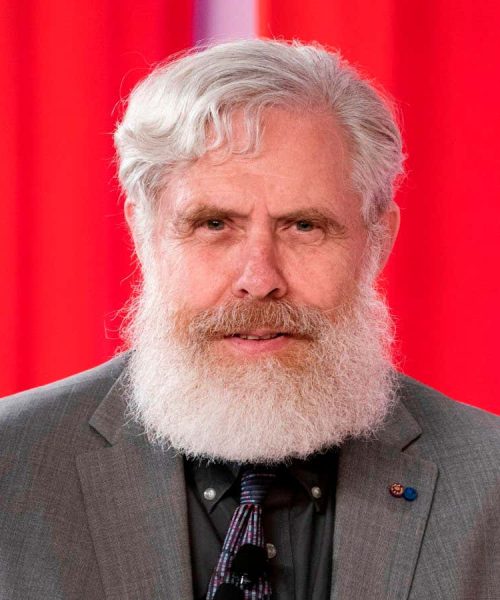

According to Colossal, they will even sound like them, though how it knows what mammoths sounded like is unclear. When it comes to their appearance, there will be at least one major difference: the vast majority will have no tusks to avoid ivory poaching, says George Church, Colossal co-founder. Those with tusks could be kept only in places with heavy surveillance, he says.

Colossal also plans to make the mammoth-like elephants resistant to a highly fatal disease caused by elephant endotheliotropic herpesviruses.

Why does Colossal need to make elephant stem cells?

The company has been editing the genomes of elephant cells to make them more mammoth-like. But to create a living mammoth-like elephant, it needs to generate embryos containing an edited genome. In theory, one way to do this is to turn gene-edited elephant cells into so-called induced pluripotent stem cells, and then to turn those into eggs and sperm cells.

What are induced pluripotent stem cells?

Pluripotent stem cells can turn into any cell in the body, including eggs and sperm. They occur naturally in embryos, but can also be made from adult cells by adding certain proteins, hence the “induced”. They have been made in many animal species, but, before now, no one had managed to induce elephant cells to become pluripotent.

Why is it hard to induce elephant cells to become pluripotent?

At least in part, it is probably because these large, long-lived animals need to have better anticancer mechanisms and that means tighter control on the growth of stem cells.

How did Colossal manage it?

Among other things, it genetically modified Asian elephant cells to permanently produce the key proteins. Even then, it still took two months to transform the cells into induced pluripotent stem cells. “We do want to make the process more efficient and faster, but I think it’s a great start,” says Eriona Hysolli at Colossal. The DNA that codes for the key proteins can be easily removed, she says.

So now Colossal will turn these induced pluripotent stem cells into eggs and sperm?

That’s the plan, but it could take many years. Turning induced pluripotent stem cells into eggs and sperm is far from easy. “It’s been done mainly in two species, which is mouse and human,” says Church. “And neither one of them is perfect.”

Does this mean it could be decades before mammoth-like elephants can be created?

Colossal claims its first “mammoth” will be born by 2028. Hysolli says the researchers aim to make just 50 to 100 genetic edits to elephant cells, which is feasible. But to generate embryos in time to meet the deadline, they will almost certainly have to transfer the edited genomes into elephant eggs using the cloning technique used to create Dolly the sheep. Because elephants have a two-year gestation period, these embryos would have to be created and implanted by around the end of 2026.

Will cloning the edited cells work?

It might, but, typically, just a few per cent of cloned embryos develop into healthy animals. “There are bound to be failed attempts. How many elephant cows will have to be subjected to the experimental pregnancies?” asks stem cell expert Dusko Ilic at King’s College London. “Just because we have the capability to do something new, that does not mean that we should pursue it without careful consideration of the ethical implications and consequences.”

Where will these mammoth-like elephants live? Given the war in Ukraine and Russia’s claims about US bioweapons, isn’t there close to zero chance of Russia allowing genetically reincarnated mammoths to be released in Siberia?

“Keep in mind that mammoths were everywhere in the Arctic circle and not just in Siberia,” says Hysolli. Alaska and Canada are also possibilities, she says, and Colossal is already having “very fruitful collaborations” with government agencies, local governments and Indigenous peoples.

Why is Colossal aiming to bring back the mammoth?

The company claims that rewilding the Arctic area with mammoths can help limit climate change by reducing permafrost melt and locking away carbon in the form of frozen organic material. “The Arctic is the perfect place to be sequestering carbon because every year it freezes another layer of topsoil,” says Church. “And then the herbivores poop on top of that.”

Could mammoth-like creatures really help limit further warming in the Arctic?

That remains to be established, but there is some plausibility. One small study suggests large herbivores can lower permafrost temperatures by flattening insulating snow in winter. And if the edited elephants limited forest expansion, that would also help, as dark trees in previously flat, snowy areas can have a warming effect by absorbing more sunshine. But many thousands would be needed to have a significant impact.

Are you saying Colossal aims to have tens of thousands of these creatures roaming the Arctic?

Yes, that is the aim. Based on the growth of elephant populations in favourable conditions, New Scientist estimates it could take a century or more to breed this many mammoth-like elephants from a small starting population.

But Church says Colossal is developing artificial uteruses that will bypass the usual limits. “So we could, in principle, do this at whatever scale the world wants and needs. If they don’t need it, then we won’t scale it up,” he says.

Topics: