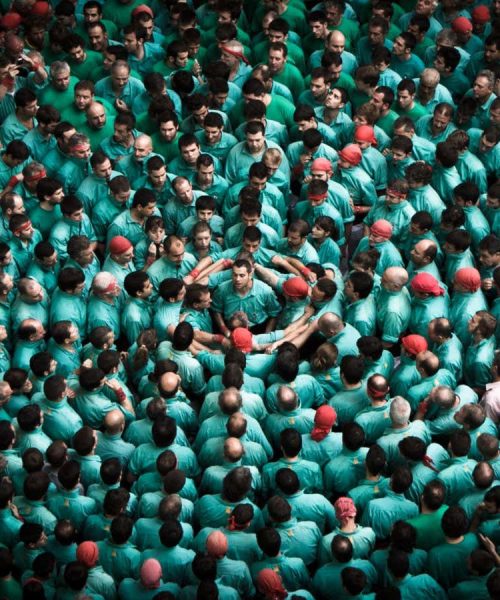

dpa picture alliance archive/Alamy

The International Space Station (ISS), as well as being the most expensive object ever made, can also lay claim to being one of the most cooperative endeavours in scientific history. Since the beginning of the century, it has been continuously inhabited by a total of 280 crew members – and counting – from 23 countries. While leaders on the ground have been squabbling or even threatening war, astronauts and cosmonauts have been circling Earth unconstrained by geopolitical borders, floating in serene microgravity.

But nothing lasts forever. Sometime around 2030, the ISS project will come to an end. From its orbit about 400 kilometres above Earth, the space station will fall through the atmosphere, burning up and splintering into a thousand pieces before crashing into the Pacific Ocean. It is unlikely that any of it will ever be seen again.

Artificial satellites reenter the atmosphere all the time – almost every day, in fact. But the $150 billion ISS is no ordinary satellite. More than 100 metres long, and with the mass of a fully loaded jumbo jet, it is by far the largest and most complicated one ever built.

Managing the end of the ISS’s life is far from straightforward. How can such a cumbersome object, all 420,000 kilograms of it, be brought down and destroyed safely? Should it be destroyed at all? And will we ever see its ilk again?

The history of the station dates back to the cultural chauvinism of the 1980s, when NASA – calling it “Freedom” – intended it to challenge the Soviet space…