Dead Planets Society is a podcast that takes outlandish ideas about how to tinker with the cosmos – from snapping the moon in half to causing a gravitational wave apocalypse – and subjects them to the laws of physics to see how they fare. Listen on Apple, Spotify or on our podcast page.

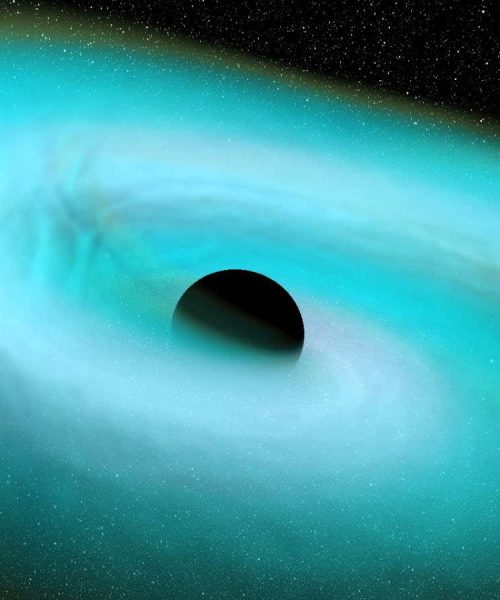

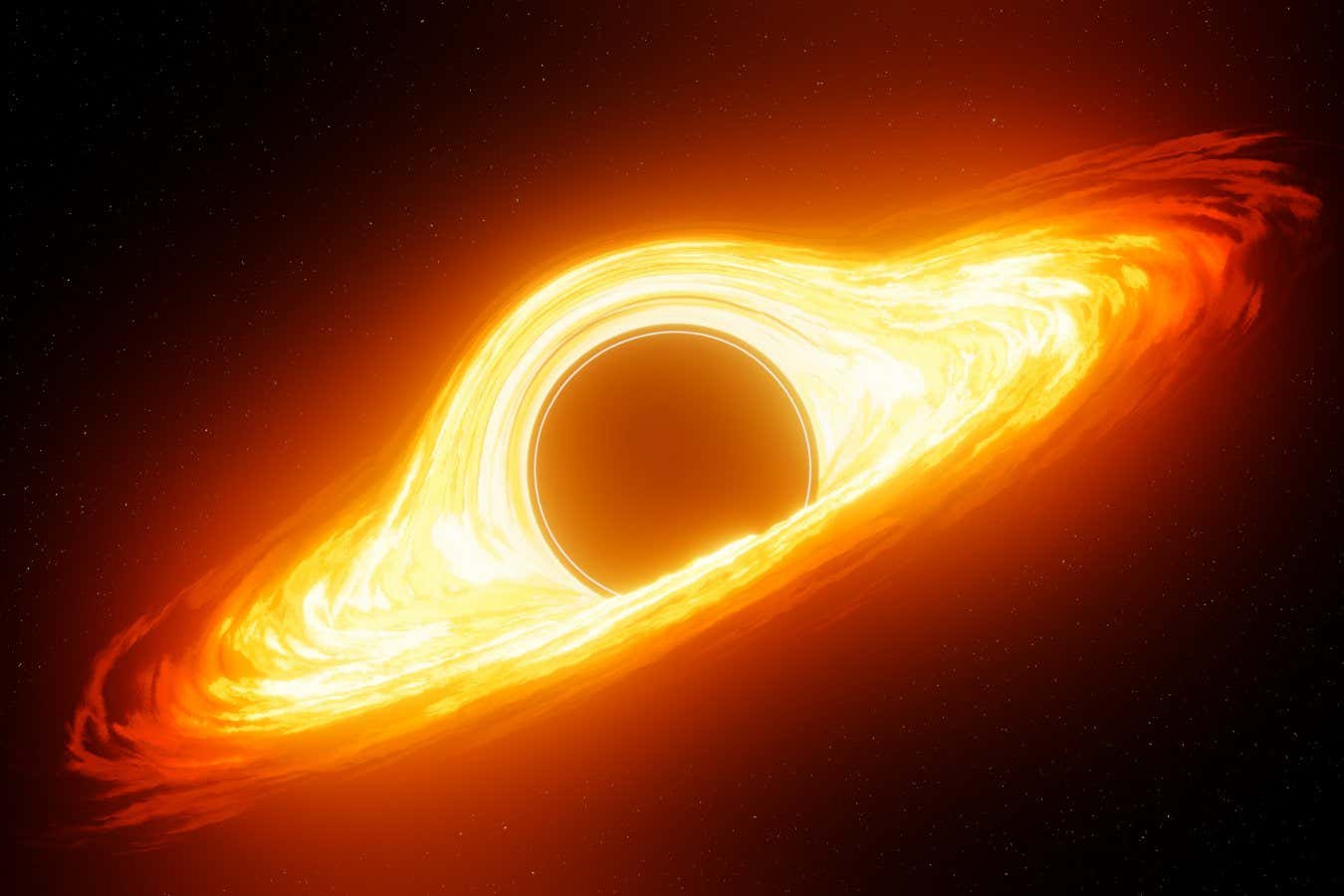

Dead Planets Society is back for season two, and our intrepid hosts Chelsea Whyte and Leah Crane are going after the toughest adversaries in the universe: black holes. These cosmic behemoths are so big and so sturdy that they can devour pretty much anything that is thrown at them without so much as flinching – so is it even possible to destroy one?

Black holes are expected to evaporate on their own thanks to Hawking radiation, a process by which they emit a slow leak of particles, but this would take much longer than the age of the universe to happen naturally. Just waiting isn’t really an option, so our hosts are joined by black hole astronomer Allison Kirkpatrick at the University of Kansas in an attempt to find a faster way.

Advertisement

Throwing anything at the black hole won’t really help either, whether it is a planet made of TNT or clumps of antimatter – the black hole will just swallow it up and get even more massive.

That doesn’t mean it is impossible to dream up something that would destroy a black hole by falling in. The escape velocity of a black hole – the speed at which one would have to fly away from its centre to escape its gravitational influence – is faster than the speed of light, so a ship that could travel beyond that physical limitation might be able to escape, or a bomb that could explode faster than the speed of light might be able to make a dent.

That is only the beginning of the outlandish ways to potentially wreck a black hole. Theoretical objects called white holes might work, but that could mean sending the black holes back in time, which wouldn’t be great for the past or the future.

A black hole could perhaps be stretched out, but whether that works depends on the question of how quantum mechanics and general relativity mesh together, which may be the biggest unsolved question in physics. Our hosts find that giant magnets could help, with potentially horrifying results.

Topics: