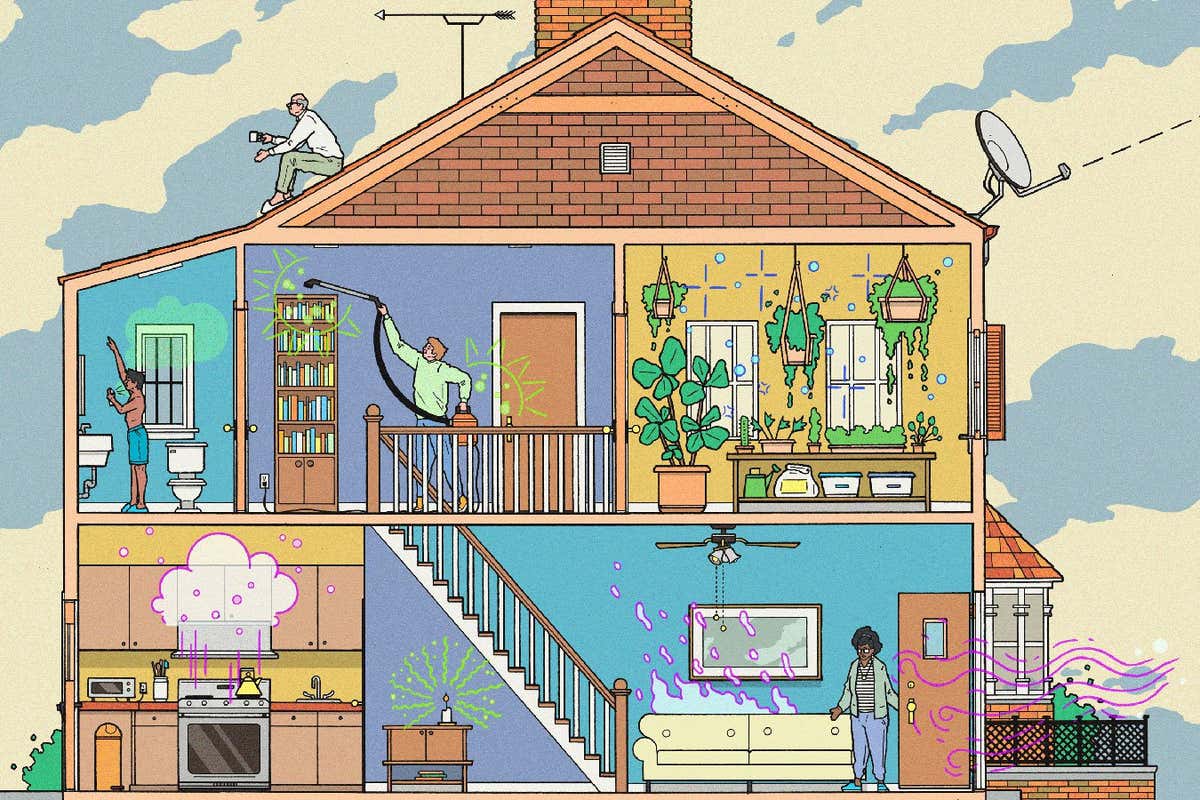

Kyle Ellingson

AS I weave through the London traffic on my bike, I always worry about the filthy air I am breathing. It is a relief to get back inside, where the air is sweeter and, you might think, better for me. But that turns out to be a false sense of security.

“People don’t imagine that there is pollution indoors; it is perceived as a protective place,” says Corinne Mandin at France’s Scientific and Technical Building Centre. “But there are more pollutants in buildings than in outdoor air.”

Thanks in no small part to covid-19, which focused minds on air quality and ventilation of enclosed spaces, the long-neglected issue of indoor pollution is finally being taken seriously. Deadly seriously, in fact, as it dawns on scientists that the pollutants we encounter in our homes, workplaces and schools are probably a major cause of illness and death. Certainly in places where solid fuel or kerosene (paraffin) are used for cooking indoors, air quality-related deaths run into the millions, hence the suspicion of harm elsewhere.

Last year, the US National Academy of Sciences (NAS) published a weighty tome on the topic, which spelled out the huge gaps in our knowledge and said that filling them was a national priority. Other countries are doing the same, says Mandin. “Indoor air pollution is having a moment.”

As this research gathers pace, and the true scale of the problem emerges, it is tempting to conclude that there is nowhere safe left to breathe. But the good news is that we can all cut exposure to indoor pollution by making a few simple changes.

As with …