Dropping the cup leads to it smashing – or does it?

Sunny/Getty Images

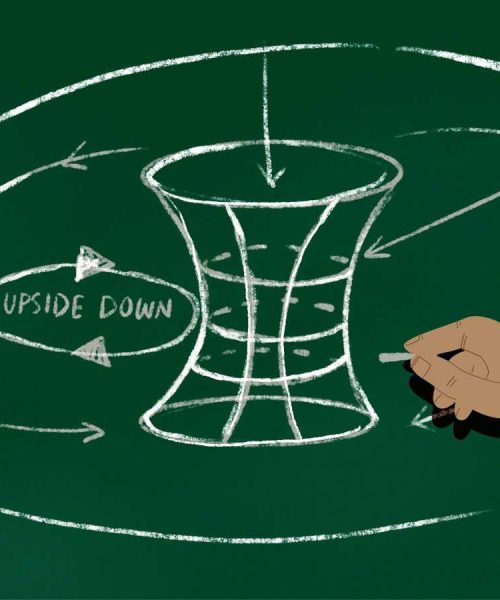

You drop a cup and it smashes. I flick a light switch and the bulb glows. Effect follows cause – it is a hard-and-fast rule of the universe. Except, perhaps, at a fundamental level. Because when we are dealing with the electrons behind the working of the light switch and the atoms in the bulb that convert electrical energy to light, causality appears to be a lot fuzzier.

In 2017, a team at the University of Vienna in Austria described an experiment demonstrating that, in the quantum realm of atoms and particles, it is impossible to say which observations were the effect and which were the cause. It was, in the words of the researchers who did the experiment, “the first decisive demonstration of a process with an indefinite causal order”.

And yet the wider research community didn’t drop their coffee mugs. On the contrary, it was welcome news for at least some of those seeking to figure out where space-time comes from. For them, a quantum theory of gravity, in which space-time would be an emergent property of more fundamental constituents of the universe, might necessarily lack the definite one-way causality of everyday life.

Space-time, as described by Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity, already has some fuzziness when it comes to defining the order of events. People moving through space and time in different ways have different “reference frames”, and those moving in different ways won’t always agree on whether event A happened before event B.…