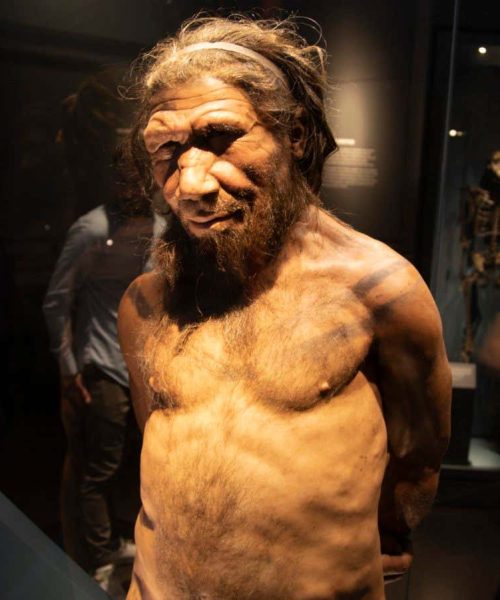

Ancient human remains are rare and don’t necessarily contain DNA

Shutterstock/Microgen

It was an otherwise ordinary day in 2015 when Viviane Slon had her eureka moment. As she worked at her computer, the results revealed the sample she was examining contained human DNA. There was nothing so unusual about that in itself: at the time, the ancient DNA (aDNA) revolution was in full swing, and surprising new insights about our ancestors were being gradually unveiled. But Slon’s sample wasn’t from human remains – it was just dirt from a cave floor. That immediately told her she was onto something big.

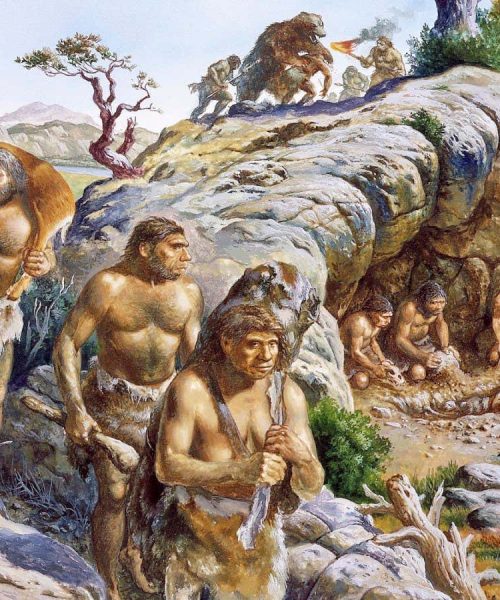

Many archaeological sites yield tools and artefacts that tell us about human occupation, but few have provided the bones or teeth that could still harbour human aDNA. Even when such remains are present, the chances that genetic material survives within them is slim because DNA is damaged by heat, moisture and acidity. So finding another source of aDNA – the soil itself – was a game changer. “That opens up hundreds of prehistoric sites that we couldn’t work on before,” says Slon.

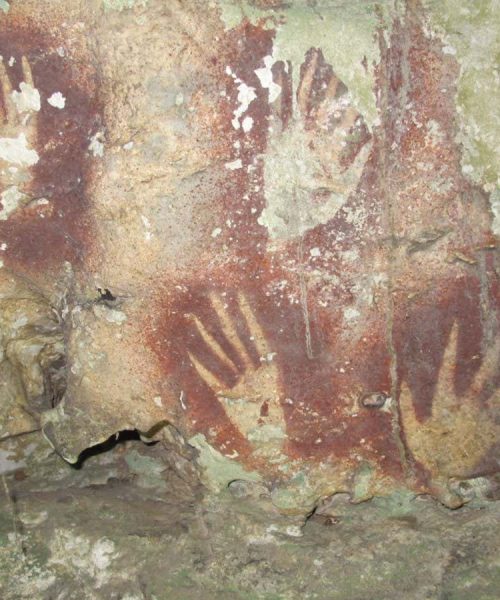

Besides, humble dirt can reveal a lot about our distant past. Whereas fossils provide snapshots of prehistory, sediment gives a DNA source that can, in theory, generate an unbroken narrative. Researchers can study hominins predating the practice of burial. They can work out which groups created particular tools and other artefacts, learning more about their cognitive and artistic…