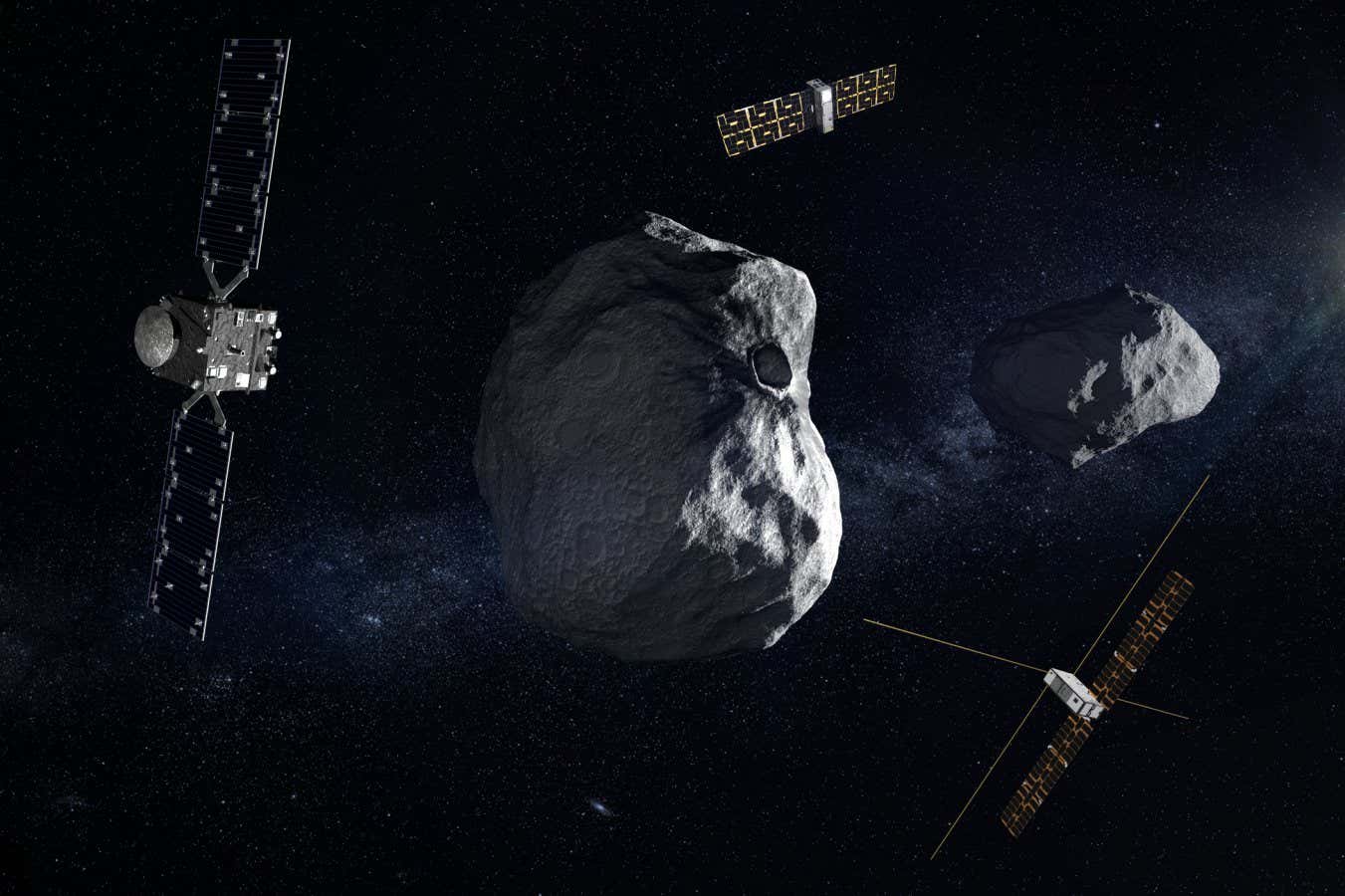

The European Space Agency’s Hera mission will study the asteroids Dimorphos aided by two CubeSats called Juventas and Milani

ESA/ScienceOffice.org

Two years after a NASA spacecraft slammed into the asteroid Dimorphos, another mission to map the space rock is about to launch. The data it collects will refine Earth’s planetary defences against asteroid threats, say researchers.

In 2022, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft collided with the asteroid Dimorphos at 6.6 kilometres per second as it orbited its parent asteroid Didymos.

Advertisement

The mission was an attempt to show that bodies on a collision course with our planet could be redirected, and subsequent observations from Earth showed that it had successfully changed Dimorphos’s orbit.

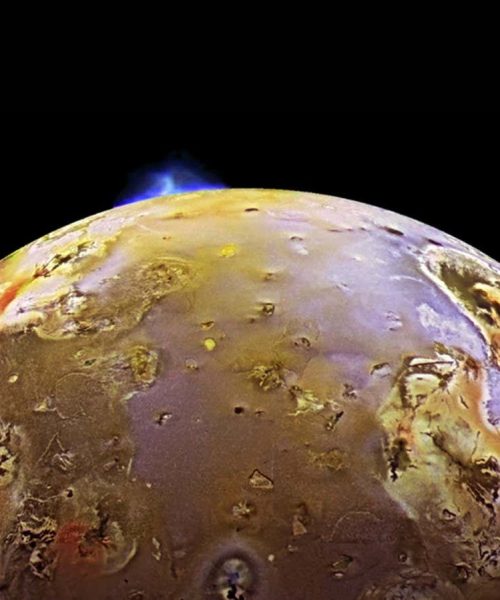

Now, the European Space Agency (ESA) is preparing to launch its Hera probe to get a closer look at exactly how it was affected. Hera is around the size of a small car, weighing 1081 kilograms when fully fuelled. It will launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on 7 October aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and do a flyby of Mars in March next year on the way to the asteroid – but it won’t reach its final destination until October 2026.

The initial concept behind the project was for Hera to be present when DART collided with Dimorphos, but delays in funding made that impossible. Despite this, the asteroid’s change in orbit was observed from Earth, and Hera’s job now is to gather more data about Dimorphos so that scientists can better understand how future impacts could be planned to deflect bodies on a collision course with Earth.

Diego Escorial Olmos, who works on the Hera mission at ESA, says DART and Hera are the basis for a planetary defence system, although more work needs to be done to improve observation – to give as much warning of incoming threats as possible – and to improve spacecraft impactors.

“It’s simple physics,” says Olmos. “If it’s huge, you need something huge to crash into it. Then again, it’s a game of timing, and again it’s basic physics: if I discover the asteroid 100 years in advance, I can just give it a small push that will be integrating over 100 years, and by the time it passes by, it misses us.”

Hera is equipped with a wide range of sensors, including thermal and hyperspectral cameras, LIDAR and radar, which will also be used to map the asteroids.

The mission will also carry two miniature satellites, or CubeSats, called Juventas and Milani. Rather than orbiting the asteroid, these will fly in front of it, making sweeping passes at progressively smaller and riskier distances to gather data. Both are expected to eventually land on the asteroid to get a closer look, once they have done all they can at a distance.

Alan Fitzsimmons at Queen’s University Belfast, UK, says the mission will “put us on the pathway to an effective planetary defence” and start to build up a model for how impacts from spacecraft affect asteroids of different compositions. But it will also be the first in-depth study of a binary asteroid, and Dimorphos will be the smallest asteroid ever measured in detail. “We can’t avoid obtaining new science at the same time,” he says.

Chrysa Avdellidou at the University of Leicester, UK, says we will need more data if we are to develop a reliable planetary defence system – although the chances of needing it are vanishingly small.

“You can go and do any demonstration that you want with these missions, but the precise outcome is very much controlled by the materials that are involved,” she says. “So a big thing that we have to do, either from the ground or with space missions, is to survey large populations of objects and understand their materials and properties of their surface. There are many more types of asteroids.”

Topics: