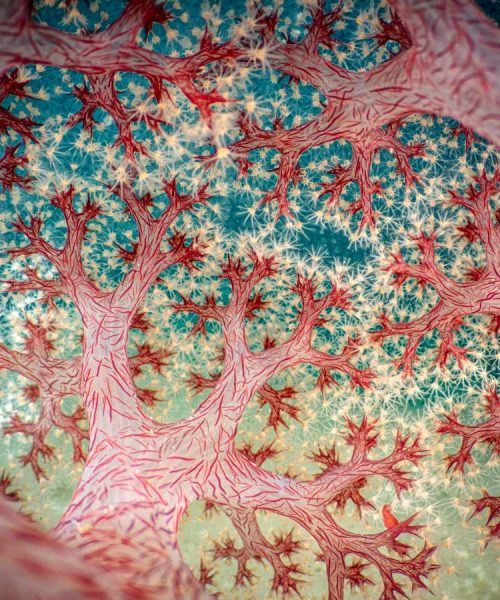

Sauropodomorph dinosaurs feeding on newly evolved plants in a wet early Jurassic environment

Marcin Ambrozik

The contents of 200-million-year-old faeces and vomit are helping show how dinosaurs took over the world at the start of the Jurassic Period.

Well-preserved plants, bones, fish parts and even whole insects embedded in widely varying shapes and sizes of ancient animal droppings suggest that dinosaurs’ broad diets made them survivors in a changing ecosystem, compared with other groups of animals. That then led them to grow larger and ultimately establish their “dynasty on land”, says Martin Qvarnström at the University of Uppsala, Sweden.

Advertisement

Fossil evidence shows that the first dinosaurs – marked notably by hip joints that position the legs under the body like mammals, rather than sprawled out to the sides like lizards – appeared more than 230 million years ago during the Triassic Period. For tens of millions of years, these early dinosaurs blended into a landscape filled with many other kinds of reptiles. By about 200 million years ago, however, dinosaurs had essentially taken over the planet, while most other reptiles disappeared during the end-Triassic extinction at around that time.

What led to this domination has remained somewhat mysterious. Qvarnström and his colleagues suspected they might find significant clues hidden in bromalites – fossilised stool and vomit – from dinosaurs and other animals. So they gathered 532 examples stored in the Polish Geological Institute, which prior research groups had collected between 1996 and 2017 from eight sites in Poland.

The team estimated the age of each bromalite based on the layer of sediment it was found in and then used its size – ranging from a few millimetres to “pretty substantial faecal masses” – and shape to match it to the animal that probably produced it. The researchers then 3D scanned the fossils to explore their contents. “We realised that they’re packed with food remains,” says Qvarnström.

Coprolites, or fossilised dung, of herbivorous dinosaurs containing plant remains

Grzegorz Niedzwiedzki

Combined with known fossil records and past climate information, the researchers determined that the rise of dinosaurs occurred in several distinct steps. First, omnivorous ancestors of early dinosaurs started outnumbering the non-dinosaurs. Then, they evolved into the first meat-eating and plant-eating dinosaurs.

At that point, an increase in volcanic eruptions and shifts in tectonic plates led to flooding and the development of waterways. The resulting humidity and related changes in the climate seem to have triggered a greater range of plants, leading to the evolution of bigger and more diverse herbivore dinosaurs. Meanwhile, non-dinosaurs – like the 1-tonne, plant-eating dicynodont Lisowicia, whose faeces contained mainly conifer remains – were less able to adapt to the changing variety of vegetation.

As the herbivore dinosaurs grew bigger, so did their predators. When large carnivorous dinosaurs started to appear by the beginning of the Jurassic Period – about 30 million years after the first dinosaurs emerged – the transition to a dinosaur-dominated world was complete, says Qvarnström.

“The study shows how climate mainly affected the dominant plants, which in turn gave opportunities for new herbivores at certain points,” says Michael Benton at the University of Bristol, UK, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Although it is hard to be sure that the researchers matched the droppings to the right animals, the findings nonetheless support earlier work from South America suggesting that dinosaur species were already significantly expanding prior to major climate change, he says. “But it took the end-Triassic mass extinction to put in place the final steps of the takeover.”

For Emma Dunne at Friedrich-Alexander University in Germany, the study helps answer long-standing questions about the rise of dinosaurs. “It’s not every day that you see fossil poop in such a high-impact journal,” says Dunne, who didn’t participate in the research. “It’s obviously funny, but it’s also really useful for understanding prehistoric environments. So if you think of early dinosaur evolution as kind of a jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces, it’s just thrown a huge chunk of new pieces in there.”

Topics: