Stephan Walter

In the 1920s, Albert Einstein thought he had found a fundamental flaw in quantum physics. This set off a chain of investigations that, over several decades, showed he had instead discovered a crucial feature of quantum theory – and one of its oddest.

This property, now called Bell non-locality, which involves quantum objects maintaining coordinated behaviours even across cosmically large distances, has been unkind to our intuition. Yet embracing it in the 21st century has turned out to be a fantastic idea.

The issue can be set out with the help of two hypothetical experimenters, Alice and Bob, who each have one of a pair of “entangled” particles. Entanglement allows the particles to exhibit correlations even if they are so far apart that no signal could ever pass between them quickly enough to make a difference. Yet, for those correlations to become obvious, each experimenter must interact with their particle. Do the particles “know” they are correlated before Alice or Bob interacts with them, or is there something spooky going on between them?

Einstein, working with Nathan Rosen and Boris Podolsky, rejected spookiness. He proposed that there must be “local hidden variables” that researchers could measure to work out how the particles were always in the know. This would make quantum physics more like our daily experience, where objects only influence each other when they are nearby.

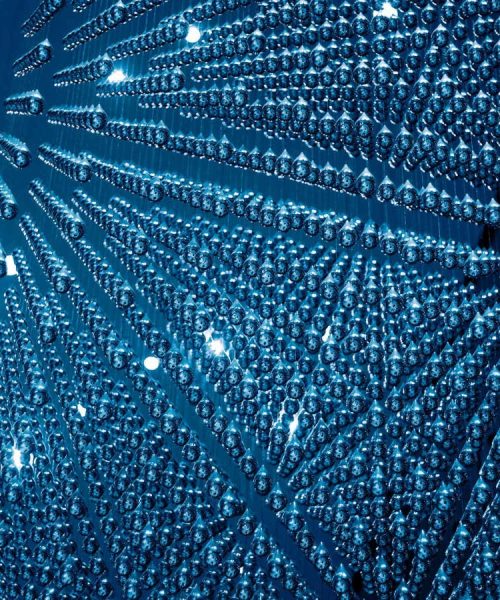

In the 1960s, physicist John Stewart Bell outlined a way to test the trio’s idea. After decades of attempts, in 2015, several experiments turned Bell’s test into reality in an unprecedentedly rigorous way, earning three of the physicists involved the Nobel prize in 2022. “That was the final nail to the coffin of all those ideas,” says Marek Żukowski at the University of Gdańsk in Poland. Hidden variables couldn’t save locality in quantum physics, says Jacob Barandes at Harvard University. “You can’t escape non-locality.”

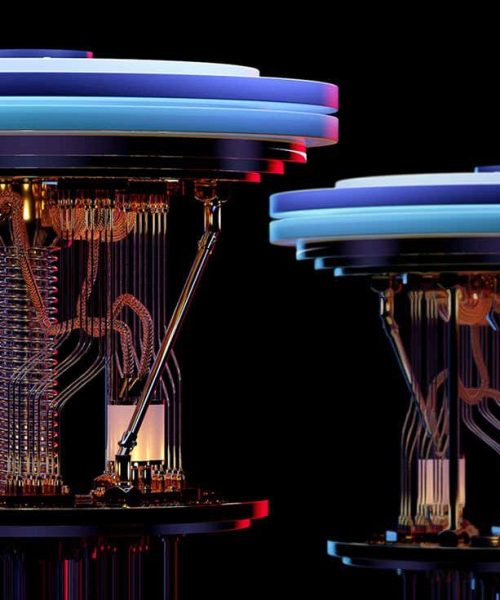

And there are real benefits if we stop trying to escape non-locality and embrace it instead. For Ronald Hanson at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, who led one of the experiments, the issue was never about spookiness. Rather, he conceived of the experiment as a feat of “quantum advantage” – something beyond the abilities of any conventional computer. His intuition bore out: some of the machinery necessary for “Bell tests” became a foundation for unprecedentedly secure quantum cryptography.

Hanson now builds quantum communication networks, leveraging entangled particles to develop a nearly unhackable future internet. Quantum computing researchers similarly use entangled particles to make computations more effective. Physicists haven’t yet fully unravelled the meaning of entanglement and are continuing to examine the assumptions that underlie Bell’s work, but entangling quantum objects reliably has become a technological resource, a stunning second act for a key player in the debate about our world’s quantumness.

Topics: