Ruby Fresson

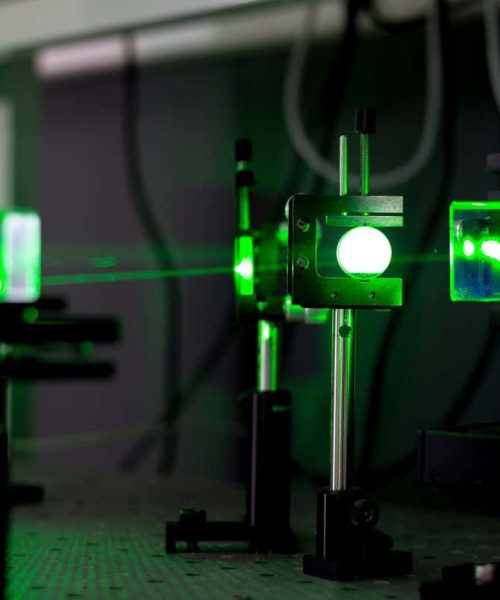

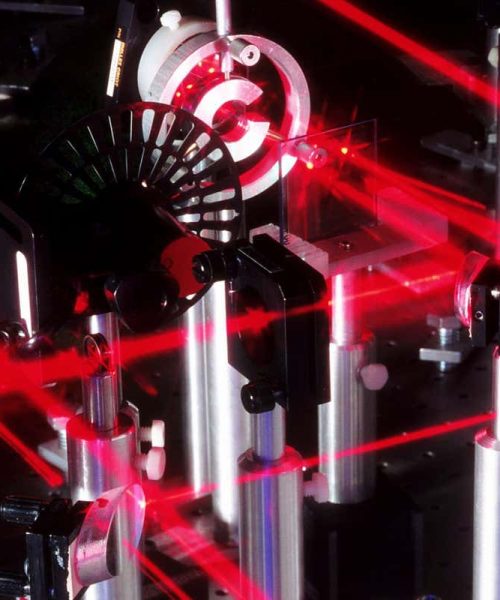

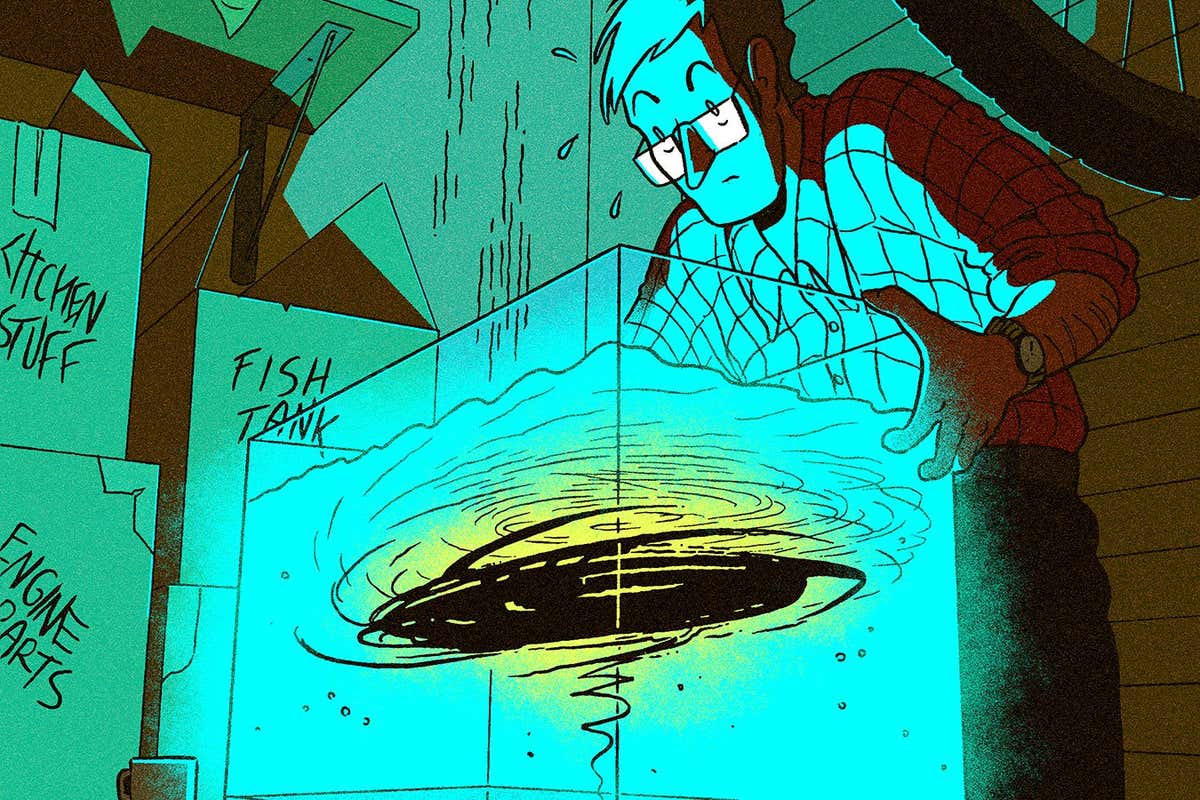

GERMAIN ROUSSEAUX owns what looks like a very long and very narrow fish tank, minus the fish. At the bottom, in the middle, is a plastic ramp. When he switches on the apparatus, waves sweep along the tank and pass over the ramp, speeding up as they do so. This, he says, is a black hole.

Well, not a black hole in the common sense. Not a star-gobbling pit in the fabric of space-time. Rousseaux’s experiment at the Institut Pprime in Poitiers, France, is a physical model of how the immense gravity of black holes can suck in waves – conventionally light waves, but in this case water waves – so they can’t escape.

It is what is known in the trade as a “gravity analogue”, and it is far from the only one. Over the past 15 years, researchers have created dozens of these tabletop models – despite the mutterings of many theorists, who are sceptical that such simple experiments can tell us anything about the universe’s most darkly mysterious objects.

Yet some researchers have begun to simulate more and more aspects of the universe, including even the entire infant cosmos. Now, some of them believe the models are giving us insights into the deepest nature of reality. There is even a suggestion that the speed of light, that hallowed constant of physics, might not be fixed after all. “Applying insights from these models would imply a radical shift in view,” says Rousseaux. But can we really rely on tanks of liquid to solve the mysteries of how the universe works?

One thing is for certain: there are many such mysteries …