We have been trying to harness the reaction that powers the stars for decades, and now private firms are promising commercial fusion within a decade. Is there any reason to believe them this time?

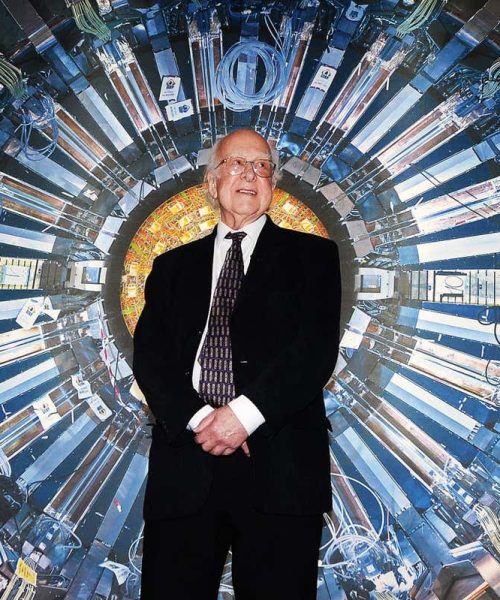

Fusion involves heating a charged gas called a plasma to temperatures approaching 200 million degrees Celsius

David Parker/Science photo library

IN MARCH 1951, the president of Argentina, Juan Perón, announced the results of a secretive project on Huemul Island in northern Patagonia. His scientists had achieved nuclear fusion, he said, harnessing the reaction that powers the sun to herald a future in which energy would be sold in “half-litre bottles, like milk”. But things soon turned sour when researchers returned from Huemul to report that the whole thing was an expensive, embarrassing fraud.

The Huemul hoax was an extreme case. Arguably, though, it set a pattern for the long quest to harness star power for virtually limitless clean energy here on Earth: audacious claims followed by disappointment, rinse and repeat. It explains the tiresome persistence of the old joke that fusion has always been 30 years away, and always will be.

Yet here we are again. In the past year alone, private fusion firms have received more investment than in the entire history of this enterprise. “The feeling among investors is that fusion will happen,” says Melanie Windridge, a fusion scientist and founder of Fusion Energy Insights, a membership organisation for the energy industry. Some companies are even promising commercial fusion reactors in a decade. “Progress is happening very rapidly,” says Annie Kritcher at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California. “As you get closer and closer, things start to take off.”

What is hard to discern, however, is whether recent advances at big, state-funded fusion projects, together with new technologies and reactor designs …