An ancient Greek bronze jar on display at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford that was found to contain honey

American Chemical Society

The contents of an ancient Greek pot found in a shrine near Pompeii are testament to the longevity of a jar of honey.

In 1954, a Greek burial shrine dating to around 520 BC was discovered in Paestum, Italy, about 70 kilometres south of Pompeii.

Advertisement

There were eight pots in the shrine containing a sticky residue, whose identity has been a mystery ever since their discovery.

Honey was an early suspect in tests carried out on the contents of one of the pots between the 1950s and 1980s, says Luciana Carvalho at the University of Oxford.

Three separate teams studied the residue but concluded that the jars held animal or vegetable fat contaminated with pollen and insect parts, rather than honey.

Back then, researchers relied on much less sensitive analysis techniques, centring on solubility tests.

Carvalho and her team began by testing the residue’s reflection of infrared light to get a sense of its bulk composition.

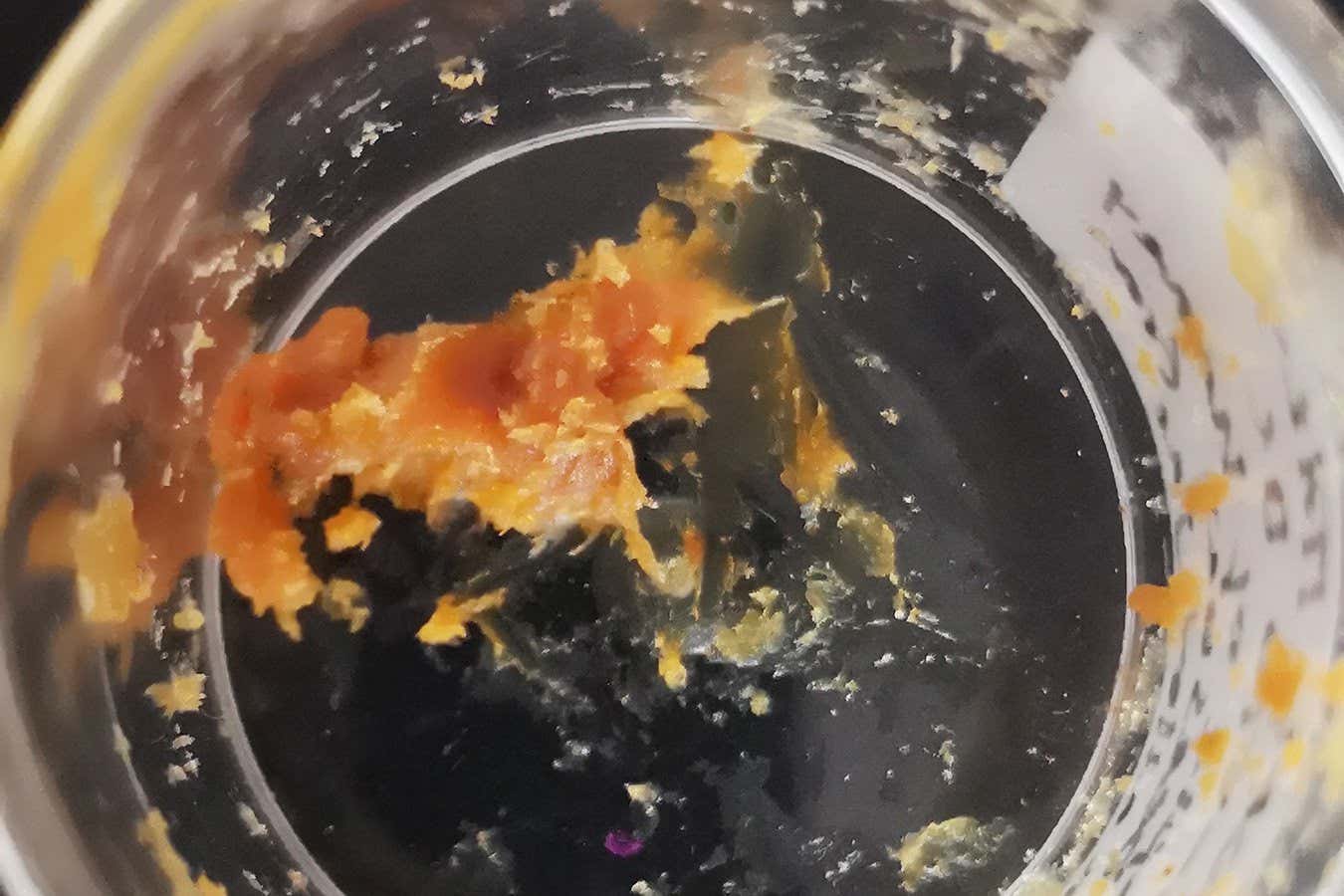

The ancient honey residue from the inside of the pot

Luciana da Costa Carvalho

At first, they thought the contents may be degraded beeswax, because of its outward similarity to modern beeswax and its high acidity.

To confirm whether this was the case, the team used gas chromatography combined with mass spectrometry. But this revealed the presence of sugars including glucose and fructose, which are the main sugars found in honey.

“We discovered a surprisingly complex mix of acids and degraded sugars,” says Carvalho. “The smoking gun for honey was finding sugars right in the heart of the residue.”

Further analysis by Elisabete Pires, also at the University of Oxford, revealed the presence of proteins called major royal jelly proteins, which are secreted by honeybees, as well as some peptides whose closest match was from Tropilaelaps mercedesae, a parasitic mite that feeds on the larvae of honeybees.

“This parasite is thought to have originated in Asian beehives,” says Pires, “so the fragment proteins we found in the residue are probably related to another type of parasite that already affected beehives in ancient Greece.”

Carvalho says the cork seals in the bronze jars would have eventually broken down, letting in air and microbes. “We think that those bacteria consumed [most of] any sugar left over, producing additional acids and breakdown products,” she says. “Over time what remained of the original residue was just an acidic waxy residue at the bottom and along the walls of the jars.”

“Confirming honey offerings in a shrine at Paestum tells us exactly how people chose to honour their deities and what ideas they held about the afterlife,” says Carvalho.

Historic Herculaneum – Uncovering Vesuvius, Pompeii and ancient Naples

Embark on a captivating journey where history and archaeology come to life through Mount Vesuvius and the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Topics: