Quantum 2.0 visits the edges of our knowledge about the quantum world

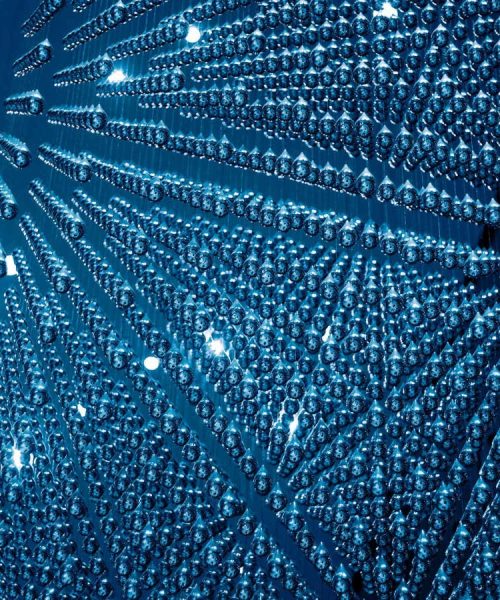

RICHARD KAIL/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Quantum 2.0

Paul Davies, Penguin (UK, out 27th November); University of Chicago Press (US, out February 2026)

Physicist Paul Davies’s Quantum 2.0: The past, present and future of quantum physics ends on a beautiful note. “To be aware of the quantum world is to glimpse something of the majesty and elegance of the physical universe and our place within it,” he writes on the book’s last page.

This romantic and inviting view permeates the book. Quantum 2.0 is a valiant effort to describe the quantum world and the very edges of our knowledge about it, and Davies is an informed and enthusiastic narrator. Yet his zeal, at times, comes dangerously close to hype, and his remarkable skill as a writer fills in gaps where a few more citations would have been more appropriate than a clever turn of phrase.

Davies’s book is extremely readable, in spite of its ambitious aim of taking on nearly every facet of quantum physics. He discusses quantum technologies for computing, communication and sensing, touches on quantum biology and cosmology, and somehow has enough time left to run through many of the competing interpretations of quantum theory.

There are no equations in Quantum 2.0, and the few technical diagrams and schematics that are included are neither cumbersome nor slow down the reading experience.

As someone who writes about quantum physics myself, I took note of how clearly Davies breaks down experiments, as well as protocols from quantum information processing and cryptography – this isn’t at all easy!

As a guide through the quantum world and all its eras, Davies is an inviting and friendly companion, and his own curiosity and excitement are undeniable. That excitement, however, isn’t always as grounded as the nuances of contemporary quantum physics research call for. Unfortunately, excitement about most things quantum, in my experience, should always come with ample caveats.

“ A reader not well versed in quantum research could mistake speculative claims for the truth “

For example, within the first 100 pages of the book, Davies twice claims that quantum computers could be used to advance climate modelling, which isn’t the consensus opinion among computer scientists and mathematicians, especially when it comes to machines we will be using in the near term.

As another example, in a later chapter that deals with quantum sensors, he notes that manufacturers of certain sensors claim that they could help analyse conditions like epilepsy, schizophrenia and autism. I waited for Davies to qualify the claim or tell me what experts who don’t sell such sensors think, but the follow-up discussion was sparse and uncritical.

As yet another caveat, I noticed that examples given during Davies’s discussion of demonstrations of quantum computers’ supremacy over their conventional counterparts were several years out of date.

A reader who isn’t well versed in quantum research – who certainly wouldn’t have a bad time reading this book – could easily mistake some of Davies’s more speculative claims about quantum research as being closer to truth. This is only buttressed by weighty proclamations such as “It’s safe to say that whoever controls Quantum 2.0 controls the world.”

To be clear, I don’t think Davies’s sentiment is incorrect. Many of the devices that power our daily lives already rely on quantum physics, and our technological future stands a good chance of being even more quantum. I am personally rooting for that.

Advances in nascent fields like quantum biology or better integration of quantum theory and theories of the cosmos also seem imminent; just ask the myriad researchers hard at work trying to formulate, for instance, a quantum theory of gravity.

But when it comes to describing this future to someone for the first time, storytelling and writing skill simply have to be paired with rigour and nuance.

Otherwise, everyone is being set up for disappointment.

Topics: