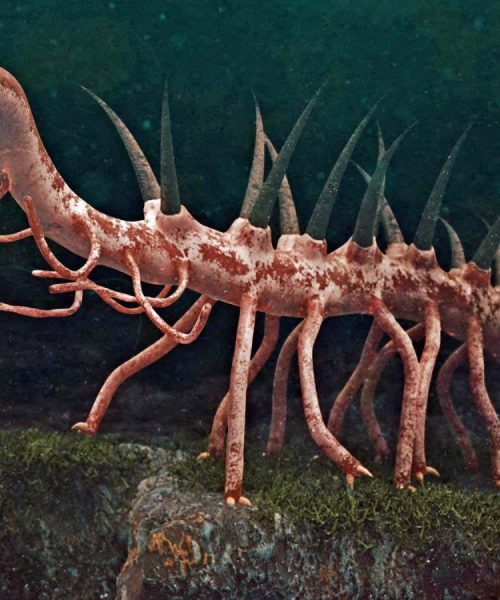

Many mushroom species produce the psychoactive compound psilocybin

YARphotographer/Shutterstock

Magic mushrooms have been giving humans mind-altering experiences for thousands of years, but the real reason fungi evolved these hallucinogenic chemicals may have been as a bioweapon against insects that feed on them.

Psilocybin is the active ingredient in numerous species of magic mushrooms, which are found on every continent except Antarctica and have a long history of use by shamans in traditional cultures. Recently, researchers have been investigating psilocybin as a possible treatment for a range of mental health conditions from depression to post-traumatic stress disorder.

The drug exerts its psychedelic effects mainly by binding to serotonin receptors in the human brain. But it has been unclear why numerous species of fungus evolved to synthesise compounds that resemble animal neurotransmitters, says Jon Ellis at the University of Plymouth in the UK. “There were suggestions that psilocybin might have a defensive role against invertebrate fungivores, but these hypotheses had never been tested,” he says.

To investigate the effects of psilocybin on insects, Ellis and his colleagues mixed dried, powdered magic mushrooms (Psilocybe cubensis) into food given to fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) larvae. They followed the young larvae through their life cycle to see how many survived, how quickly they developed and whether the adults were smaller than average or showed signs of developmental differences.

They also prepared liquid extracts from the mushrooms, added some sucrose and exposed larvae to these extracts for an hour before filming how they moved. It was “a bit like a bath in a sweet magic mushroom soup”, says team member Kirsty Matthews Nicholass, also at the University of Plymouth.

“By measuring how fast they crawled, how far they travelled and how coordinated their movements were, we could quantify short-term effects on the insect nervous system,” says Nicholass.

The larvae raised on food containing magic mushrooms survived at far lower rates than larvae given normal food. At lower doses, survival to adulthood dropped by more than half, and at higher doses only about a quarter of the larvae survived.

“Even among those that did make it through development, the effects were clear: adult flies were smaller, with shorter bodies and asymmetries between the left and right wings, which is a classic sign of developmental stress,” says Nicholass. “They crawled shorter distances, spent less time moving overall and showed more erratic turning behaviour. In practical terms, this means the insects were slower and less coordinated.”

But it is unlikely that insects would have a psychedelic experience like those humans have, she says. “What our results suggest is that compounds like psilocybin interfere with basic insect physiology and behaviour in ways that are likely harmful rather than mind-altering.”

The team also collected seven mushroom species from Dartmoor, UK, and analysed the invertebrate DNA present on the samples. This revealed that the psilocybin-producing fungi collected hosted a distinct group of insects from most of the other fungi sampled, suggesting that psychedelic compounds may play a role in shaping which insects can live in or feed on them, the researchers say.

However, there were some unexpected results, indicating that psilocybin’s role is more complicated than the results first suggest. For example, fruit flies with reduced levels of the serotonin receptor that psilocybin normally interferes with suffered worse effects.

The researchers say other hypotheses about the evolution of psychedelic fungi should also be tested, such as the idea that psilocybin deters slugs and snails or these fungi manipulate invertebrates to help them disperse spores.

Fabrizio Alberti at the University of Warwick in the UK says the experiment shows that even mushrooms that don’t make psilocybin can produce other metabolites that interfere with insect pupation rate and survival.

“Further studies using pure psilocybin on insects will be needed to pin down the ecological role of psilocybin and investigate if this hallucinogenic compound may have evolved as an insect defence,” says Alberti.

The study highlights the major challenges in exploring the evolutionary role of psilocybin-producing fungi, says Bernhard Rupp at the University of Innsbruck, Austria.

“There are many ways in which mushrooms producing psilocybin and other exotic compounds might gain an evolutionary benefit, such as deterring consumption by insects or snails,” he says.

Insect and ecosystems expedition safari: Sri Lanka

Journey into the richly biodiverse heart of Sri Lanka on this unique entomology and ecosystems-focused expedition.

Topics: