Steve Nelson

In June 1972, the Royal Society of Medicine in London hosted a symposium called “Man in His Place”. It featured an eclectic group of speakers, including Jacob Bronowski, whose acclaimed 13-part BBC television series, The Ascent of Man, would air the following year. But the first person to take the podium was John Bumpass Calhoun from the US National Institute of Mental Health outside Washington DC.

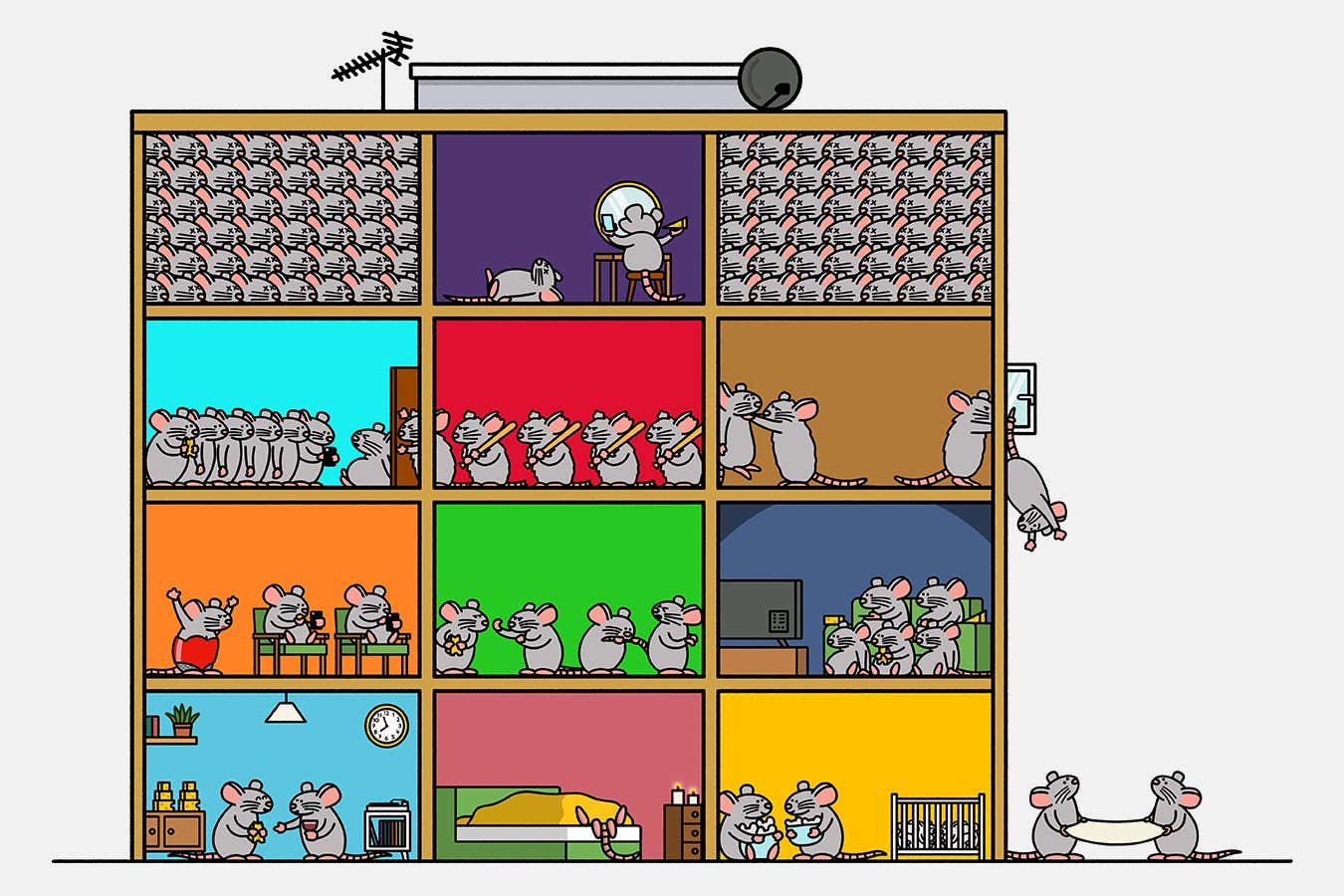

Even audience members familiar with Calhoun’s work had no idea what was in store for them, and the title of his talk – “Death squared: The explosive growth and demise of a mouse population” – didn’t give much away. “I shall largely speak of mice,” he began, “but my thoughts are on man, on healing, on life and its evolution.” He then went on to describe a long-term experiment he was running on population dynamics involving mice living in a “Utopian environment” that he dubbed Universe 25. Although his study subjects were rodents, Calhoun believed his metropolises had implications for humans: this was a cautionary tale of the chaos and social collapse in store for humanity in an overpopulated world.

An ecologist-turned-psychologist-turned-futurist, Calhoun became a science rock star in the 1970s. His message struck a chord at a time when the human population was expanding rapidly and overcrowding was a hot political issue. As interest grew in his research, Calhoun was courted by the great and the good, from politicians and urban planners to prison reformists and writers. He even had an audience with the pope. Strange as it may seem, his rodent cities…